The North Island’s second highest peak cuts a striking figure. A classic stratovolcano, it is one of the most symmetrical conical-shaped mountains in the world. For half of the year Taranaki is clad in snow, yet its 2,518m summit is just 26km from the Tasman Sea. It has been a movie star, playing Mt Fuji in The Last Samurai, graced the cover of Lonely Planet, and was voted by travel guide experts in 2017 as being the second best region in the world to visit.

The lure of New Zealand’s Mt Taranaki is undoubtedly powerful, but despite its good looks it’s not a place to be trifled with. The main route to its summit claims the title as being the trail third most commonly involved in search and rescue operations in the country – around 25 each year – mostly due to ill-prepared or ill-equipped walkers.

My buddy Andy and I are keen to climb it for ourselves, but before attempting any summit bid it seems only wise to spend some time scoping out the objective. The Pouakai Circuit is our chosen vantage point, a 25km hiking trail nestled in the cradle between Taranaki’s northern flanks and the Pouakai Range. Touted as one of the park’s premier tramps, the two to three day loop promises stunning terrain and regular glimpses of the mountain.

A HIDDEN GIANT

A few kilometres from the Egmont Visitor Centre, the trailhead immediately deposits us in thick montane forest where ferns mingle with rimu and twisted and gnarled kamahi trees, covered in rich green moss and dripping with epiphytes. A narrow mesh suspension bridge reaches across the Waiwhakaiho River which burbles over polished boulders before disappearing through a sheer sided canyon.

Officially, the trail climbs up the Ram Track to sidle beneath the impressive lava columns of the Dieffenbach Cliffs, and on across the Boomerang Slip – described in the trail notes as an ‘active erosion scar’ – but so active is the slip that the trail has been diverted up the far less trodden Kokowai Track. It’s rough and slick with dark mud, and we haul on tree roots and hiking poles to drag ourselves up a long and viciously steep ridgeline.

Eventually tangled forest gives way to low shrubland and our view expands, but Taranaki is hidden in mist and all we can see are the densely cloaked ridges of its lower flanks. Cuttings along the trail edge, revealing centuries-old layers of compacted volcanic ash and rock, provide only a tantalising glimpse of the giant we stand on.

ALL HAIL THE MOUNTAIN

We spend the night at Holly Hut, basic but homely, and in the morning get our first clear view of the mountain. It’s every bit as awe-inspiring as we’d imagined. Dark green flanks are cut with long deep striations radiating towards us, carved by pyroclastic flows and water erosion – unsurprising considering the seven metres of rain that fall here each year.

Taranaki is the fourth cone to form in this dynamic region, following others that have risen and collapsed before it over millennia. Ash from its eruptions has been found in lakebeds as far away as Auckland, 250km north, though these days it’s considered dormant and the last major eruption is estimated to have occurred in the late 1700s.

From the hut, we descend to the vast flatlands of the Ahukawakawa Swamp – 3,500 years old and filled with sphagnum moss – before climbing again into the Pouakai Range. By mid-morning we’ve already reached our next hut but on this day it’s not about the walking, it’s about the watching. Nestled amongst the tussock on an open ridge, just fifteen minutes from the hut, is a tarn. From the trail it doesn’t look especially striking but, when you’re positioned behind it, the dark surface of its shallow water reflects the mirror image of Mt Taranaki.

It’s the money shot, the image worthy of a guidebook cover, the view that has Instagrammers frothing with excitement. There are a dozen of them already there when we arrive, flying drones and waving selfie sticks, all the while ignoring signs imploring them to stay on the boardwalk. But at midday the cloud hangs low, obscuring Taranaki’s peak, and the view is only half of what it could be.

“I find around 6pm or first thing in the morning is best,” says the ranger stationed at Pouakai Hut. “That’s when the weather always seems to clear.”

Day-trippers can reach the tarns via a two-hour walk from a road, but staying here overnight maximises the chances of catching the mountain at a good moment.

By sunset we’re in luck. The cloud lifts and we shoot a dozen photos of our own – okay, maybe fifty – trying to find the perfect composition, the perfect pose. We swap jackets – Andy’s bright blue one contrasting far more strikingly than my dark red one against the backdrop.

In the early morning there is not a cloud in the sky nor a breath of wind ruffling the tarn. It looks even better than it did the night before, so we do it all again, just as starstruck by the mountain as everyone else who lays eyes on it.

MOVING ON UP

Reluctantly we leave the tarn to climb a ridgeline to Henry’s Peak, the track so steep in places that half a dozen ladders have been installed. The view is epic. A tide of white cloud rolls in from the east, lapping at the mountain’s base and slowly creeping up its flanks, as it does most days. For a good half hour we soak it up, studying every crease and line in the mountain’s body, wondering what it will be like to tackle the ascent to its peak. Tomorrow we’ll find out.

The coastal town of New Plymouth, a half hour drive away, is the main access point for Egmont National Park and we overnight there with a friend of a friend who has offered to put us up. As a local, Russell knows the mountain well. He’s unassuming, speaking with quiet respect for Taranaki.

“It gets real cold up there,” he warns us gravely. “Have you got warm clothes?” We reassure him we do. “What about waterproof pants and jacket?” Check. “Hiking poles?” Yup. “Gloves?” We borrow some. “Take everything you’ve got. It changes real quick up there.”

There are 1,600 metres of elevation to be gained on the 6.3 kilometre climb to reach the summit, plus there’s the matter of altitude itself. I wasn’t anticipating an easy day but by the time Russell’s finished his brief I’m considerably more anxious about the prospect.

SUMMIT FEVER

We leave not long after 6am from the Egmont Visitor Centre, climbing a 4WD track lit by the beam of our headtorches all the way to the treeline. The rising sun sends a wash of dark orange across the horizon and, about 150km distant, Mt Ruapehu – the North Island’s tallest mountain – and the conical Mt Ngauruhoe of Tongariro National Park are the only obstructions to rise above the low sea of cloud flowing between us.

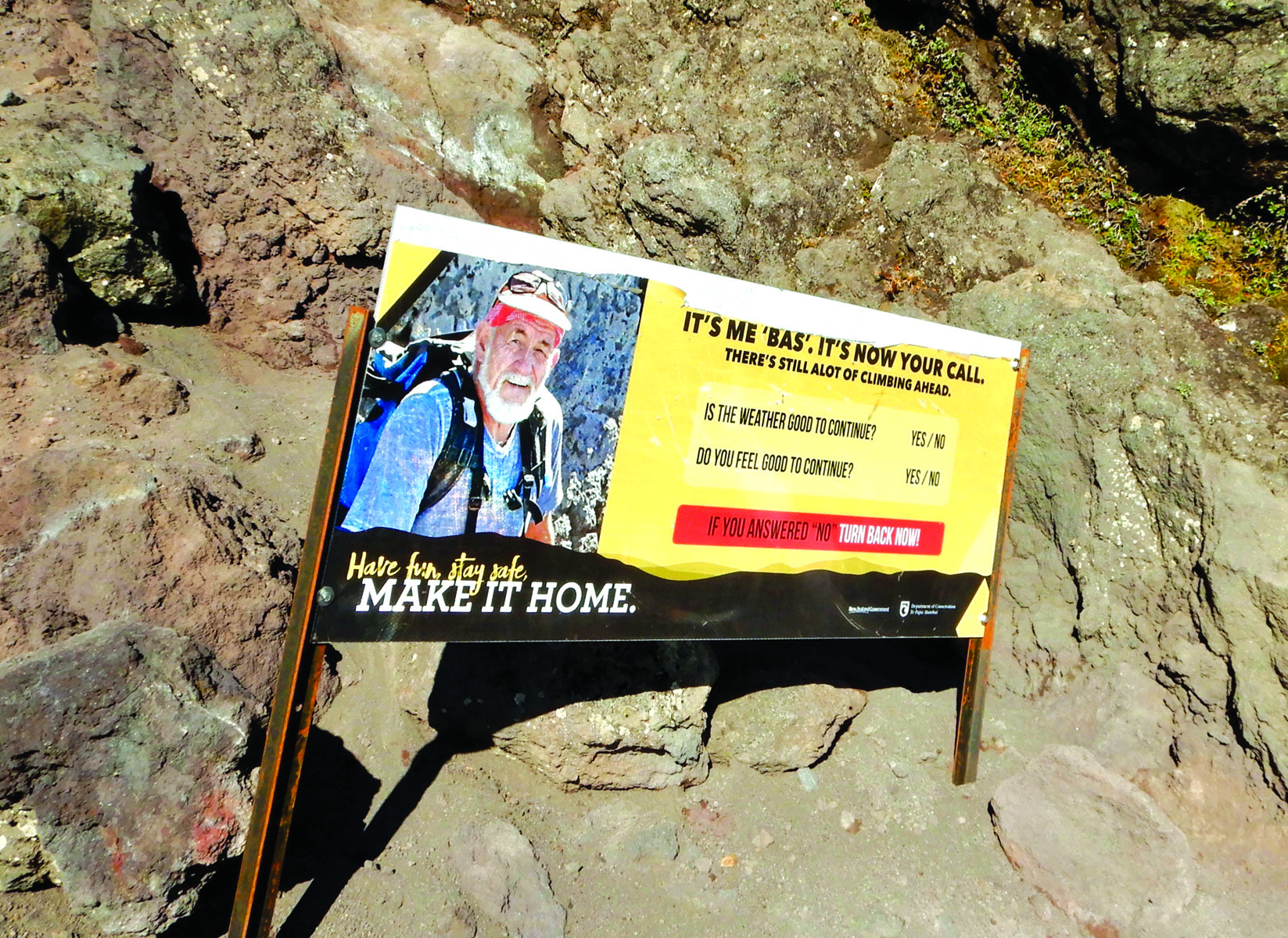

It takes an hour to reach Tahurangi – a private lodge belonging to Taranaki Alpine Club – and it’s from here that things get serious. The trail diminishes to a boulder-filled route up the Hongi Valley followed by long flights of steps to meet the base of a vast scoria slope. There to greet us is ‘Bas’, a rugged outdoorsy looking man pictured on a large sign informing us that it’s still a long way to the top. “Is the weather good to continue? Do you feel good to continue?” he asks. “If you answered ‘no’, turn back now!”

The scree is challenging. Loose balls of scoria roll underfoot like ball bearings and the gradient is so acute it’s hard to retain grip. For an hour we ascend, following sporadic orange marker poles, and then find ourselves at the bottom of a steep ridge of rock referred to as The Lizard. ‘Bas’ is there again, asking us if the weather is still good, whether we still feel good. It is and we do, so we push on, scrambling on all fours in places to climb the mountain’s flanks. Beneath us the sea of white cloud thickens, reducing our view to bare grey rock and blue sky. The scene looks like something from an aeroplane window.

After another ninety minutes The Lizard is done and we scramble around a rock ledge to traverse an ice-filled crater before the final push to the summit. I’m elated to reach it, not least for the small yet secure patch of flat ground that it offers. Ripples of cloud flow to the horizon, mingling with blue haze and occasional glimpses of forest far below. On a good day you can see all the way to the South Island. A halfpipe of ice separates us from a jagged pyramid-shaped ridge of rock called the Shark’s Tooth. To the north we trace the entire Pouakai Circuit.

We are lucky – the dreaded wind and cold we were warned about is absent and we laze about until the thought of the building cloud drives us into action. As any mountaineer will attest, getting to the top is only half way.

IT AIN’T OVER ’TIL IT’S OVER

The descent is a marathon of concentration, of balancing on rocks and searching for footholds. The scree is a nightmare. At one point both feet start sliding downwards of their own volition, prompting a mild panic, and I turn my toes inwards into a ‘snowplough’ to try and arrest it. Other walkers pass us, still on their way up, dressed in shorts and singlets – some without backpacks. I don’t think Bas would be happy about that.

On the scree, the cloud eventually catches us, reducing my world to the ten metres around me. It feels a quiet and lonely place. A solo man in his 50s trudges upwards, pausing to rest every few steps, clearly exhausted. “It gets steeper,” I warn him doubtfully. “Yes, it is steep here,” he replies in faltering English. Andy and I pause, knowing what he’s still to face. The man takes another step and stumbles, almost falling over. “Are you alright?” Andy asks. “Yes, yes,” he says, staggering on until he’s swallowed by the mist. There is nothing we can do.

Down, down we go, back to the relative safety of the steps and the Hongi Valley, down the 4WD track and to our waiting car. The descent takes almost as long as the climb.

Taranaki couldn’t have been kinder to us and yet I’m glad when it’s done. I’ve been bitten by New Zealand’s elements before, by cutting temperatures, unexpected snow, and wind that literally blew me over. They are moments that become burned into your psyche, ensuring you’ll do your darnedest never to repeat them. They have made me far more cautious when heading out into the wilds. On a mountain like Taranaki, there would be nowhere to hide if shit got real.

There is no questioning her beautiful lines and magnetic attraction but this is one siren song you don’t want to fall for.