Travelling through time can be a complex affair. Acceleration beyond the speed of light will transport you forwards and possibly backwards (there’s disagreement about whether or not moving backwards in time is possible); so too will entering wormholes in deep space. But I’m here to say the answer lies not in physics but in a half decent pair of boots.

Seems absurd, but this is exactly what happened while walking along the Green Gully track. My footwear carried me backwards through the ages. It wasn’t fleeting either, this sense of travelling to another time. It was persistent, sending me deeper and deeper into 1930s Australia with each step; back to when Alan Youdale purchased a pastoral lease holding from the Crown and began breeding and driving beef cattle through a section of undulating and unrelenting NSW bush.

Ostensibly, the Green Gully track is a 65 kilometre loop that takes about four days to complete. But there are a number of factors that elevate the Green Gully track beyond mere bushwalk and into quasi-interactive sojourn into the past. National Parks and Wildlife Services NSW (NPWS) and particularly the driving force behind the track’s creation, ranger Piers Thomas, have painstakingly restored the route to closely mirror what it was like to live in the area, decades ago. Each night, walkers bunk down in huts originally built by stockmen and women who, in the mid-twentieth century, worked and lived on the surrounding land.

Of course, before European arrival, the area was home to the Aboriginal Dhan-Gadi people, and certainly for them the arrival of Europeans was existentially devastating. First came violence, regularly wreaked upon them by their colonist oppressors, then sickness – a smallpox epidemic in 1830 decimated untold thousands. The history of Aboriginal interaction with colonial pastoralists is a bloody, tragic and critical Australian story in its own right, but for this purpose (explaining an experience walking the Green Gully track) it’s a whole other subject, best left for another forum.

Before Alan Youdale, from the early nineteenth century onwards, there was certainly other European pastoral activity in the area, but due to a number of factors, including the region’s inhospitable nature and remoteness, details of that time are not as readily forthcoming. Piers Thomas, in restoring the huts, hopes the history of the twentieth-century pastoralists – their life and death struggles in the wilds of the New England High Country – isn’t forgotten. “I think it’s vital to understand and appreciate the way these people lived,” he tells me later.

Alan Youdale was born in New Zealand in 1900. In 1920 he visited Australia and decided not to return home. In 1931, together with his mate, Paddy Hongo, a sleeper cutter and grazier from nearby Walcha, he managed to purchase a lease that included all the land around Green Gully. The first hut in the area, now known as Youdales hut, was built by Paddy and Alan in 1941. It’s around this time the O’Keefes became involved in the area, with Laurie O’Keefe acquiring a stake from Youdale. Together, the Youdales and O’Keefes drove beef cattle through the area for close to 50 years. Laurie O’Keefe and his son, Jeff, built the five stockman huts that now comprise the rest points of the Green Gully track.

A COTTAGE, THREE HUTS AND A LODGE

The Green Gully Track begins at Cedar Creek cottage. We arrived via car, parked, unloaded and spent the afternoon chilling out, stretching calves, chattering, consulting maps. The final encampment, Cedar Creek lodge is a little further down the road. Cedar Creek cottage and Cedar Creek lodge are where the 65 kilometre loop begins and ends. An ouroboros in the bush.

During the late afternoon, a group who had just completed the track arrived at the lodge and flicked on the lights. It was an odd, almost foreboding feeling, standing outside by our fire staring at a perfect square of light in the darkness made by their lit window. Occasional laughter drifted across the space between their lodge and our cottage. The mood for us was altogether more serious, our laughter not so garrulous. We hit the hay early with the distant window still lit.

When we awoke the next morning, we waited for them to leave, then moved our car down so it was beside the lodge. There’s a fridge in the lodge and in it we placed three steaks, new potatoes, some salad greens and a six-pack of local artisanal lager. They’d be the source of our laughter four nights’ hence.

THE GREEN GULLY TRACK

First up, walkers spend the afternoon and night preparing for what, ultimately, should prove to be a physically challenging adventure that tests endurance and basic bushcraft. Walkers carry everything but water with them – food, sleeping gear and other essentials. Water can be replenished from rainwater tanks stationed at each hut. All the days are either steep uphill or savage downhill on often unmarked trails, except for day three.

During day three, walkers remove boots and don sandshoes for a day spent walking in the bottom of Green Gully gorge, crisscrossing and occasionally traipsing through the creek itself. While in the Green Gully, the time-travel sensation drops the relatively recent stockman guise and instead transports walkers to a far more ancient era. Rarely sighted brush-tailed wallabies stare curiously from rock ledges, birds are everywhere and the odd black snake or two slithers away from crashing feet, annoyed at having its sunbathing interrupted.

The first working stockman’s hut encountered, after a five hour undulating amble along Kunderang Trail, is Birds Nest hut. It’s a neat short rectangle with a fairy-tale triangular roof. It looks like the type of house pre-schoolers draw, even down to its chimney stack. It’s clad, walls and roof, in sheets of corrugated iron and the floor is hard compacted mud. Afterwards, Piers tells me it’s a tricked-up mixture of mud and other binding agents to prevent it from transforming into a quagmire. Perhaps the only modern concession to comfort. Back in Youdale and O’Keefe’s time, if the floor got muddy, well, it got muddy. Inside the hut are six neatly stacked camp beds, another modern concession. In fact each of the huts is replete with six camp beds, a gas stove, cutlery and crockery.

All around, on the interior beams, on the walls and hanging from the rafters are old horseshoes, bottles, cans, rusted but serviceable stockyard tools and even old posters from the 60s and 70s. It creates an ambience where you half-expect a Youdale or an O’Keefe to come bursting through the door at any minute, looking for a cup of tea.

In fact, each of the huts during the next two nights are similarly crafted. Corrugated iron cladding over both walls and ceiling, a hearth, a dry woodpile tucked to the side with accompanying splitter and axe, a picnic table and an outside fire-pit. The hut on night four, Colwells hut, has floorboards rather than hard-packed mud.

The real accomplishment of these three central huts (Birds Nest, Green Gully and Colwells) is how, through sensitive restoration and the addition of a booklet in each detailing their individual histories, they fully engage the senses, providing an unerring glimpse into the past.

ALAN YOUDALE UNHORSED

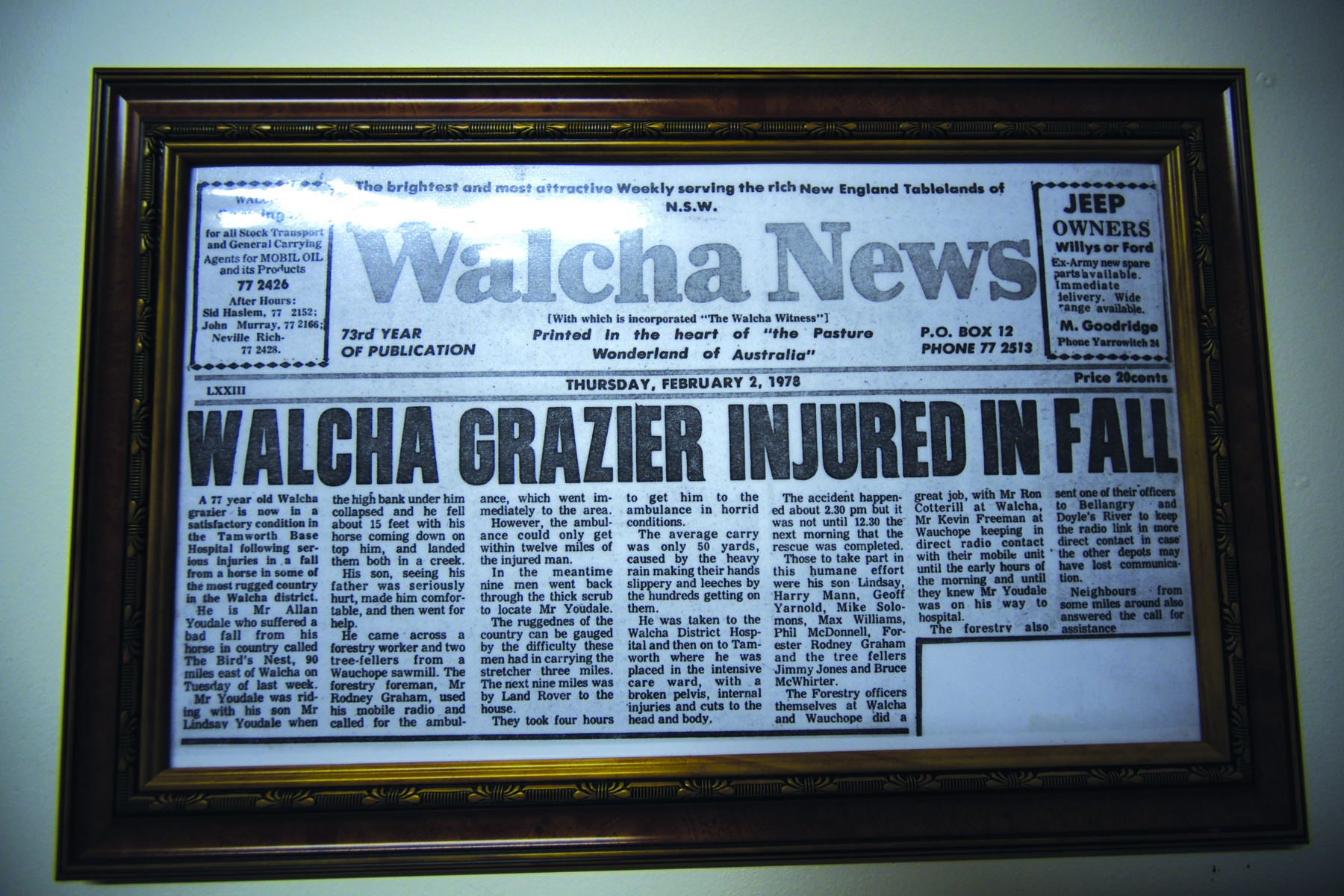

Perhaps the most immediately riveting account discovered in the huts chronicles the near-fatal accident that befell Alan Youdale in 1978. While out with his son, Lindsay, mustering cattle in the driving rain, the ground beneath his horse suddenly gave way, causing both rider and horse to fall into a steep ravine. He became unsaddled, his horse landing on top of him. Spooked, the horse tried to regain its feet, hooves flailing powerfully into thin air, searching for solid ground. They eventually gained traction against a prostrate Youdale, thudding into his chest, cracking his ribs and puncturing his lungs. The fall had already broken his pelvis. Alan Youdale was 77 years old when this happened. He lay in the cold, wet mud for 15 hours while his son went for a help. He was in hospital for three months. The accident made front-page billing in the Walcha News:

“Nine men went back through the thick scrub to locate Mr Youdale. The ruggedness of the country can be gauged by the difficulty these men had in carrying the stretcher three miles. They took four hours to get him to the ambulance in horrid conditions. The average carry was only 50 yards, caused by the heavy rain making their hands slippery and leeches by the hundreds getting on them”.

TIME INSIDE YOUR HEAD

Like most good long walks, there’s plenty of time to ruminate on everything and anything. Along with “what bird is that?” and “I should do some more running, my legs are useless”, my imagination marvelled at the toughness of Alan Youdale and the O’Keefes, but also wondered, perhaps alarmingly, about what they’d make of something like botox, of it being injected into their wrinkled faces at a shopping-centre clinic. What they’d make of My Restaurant Rules if they happened to be a contestant. How they’d feel being berated by Manu over a collapsed cheese souffle.

Toughness and luxury back then were one and the same. A tough life was a good life, well spent. A hard day’s work while astride a good horse was, for many, the key to success. After all, there were scant few office jobs back then. It’s easy to forget the comfortable suburban life, so ingrained in us now, was a completely new phenomenon back then. Before 1950, vast tracts of housing with centralised supermarkets and commuter routes organised around places of work was a fanciful concept. No, for the Youdales, the O’Keefes and others like them, it was best to work hard, acquire some land and then use it to not only generate income, but also to provide a life worth living.

Time in the wilderness makes you think. Having the senses fully engaged sharpens the experience, whatever it may be. I thought upon things that have happened so far. What remains clearest and most fulfilling are the times spent fully focussed on what’s at hand. It may be an uncomfortable experience – cold, wet, dark, dangerous. I can remember being out of control in the middle of the ocean, my mate riddled with sea sickness reefing mainsail, spewing occasionally, while I wrestled with the tiller, a jumble of waves buffeting us back across beam causing uncontrollable gybing. It was beyond dark, pitch black in the truest sense. The wind was screeching through the rigging. The luffing sails whipping. We were screaming at each other. We gybed three times before we were able to reduce our sail area.

Experience. Are you experienced? I asked myself this question as I leaned out over the verandah railing of Cedar Creek lodge, the sweet froth of an artisanal lager touching my lips.