Half a billion years after forming, Australia’s most recognisable natural feature – Uluru – is about to embark on a new beginning of its own.

When climbing “The Rock” is banned from 26 October 2019 – the 34th anniversary of the Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park handback to its traditional owners, the Anangu – not only will its cultural significance be respected, but its sensitive environmental habitats too.

Even from a distance, the weather-beaten slab has been clearly sculpted by millions of years of rain and wind, etching stripes between the almost perfectly vertical sandstone layers.

But in the past six decades or so, another phenomenon has shaped the rock. Hundreds of thousands of pairs of shoes have stamped what traditional owner Sammy Wilson called a “scar” in Uluru’s rugged north-west face.

Uluru is world heritage-listed for its cultural and natural values, interwoven for tens of thousands of years, Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park manager Mike Misso says.

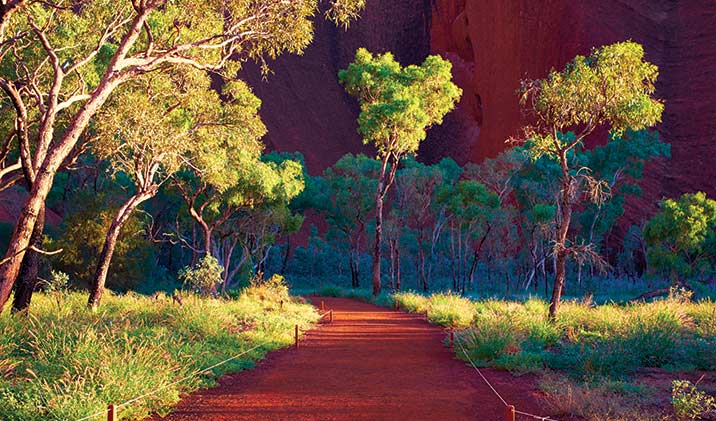

"Because it’s a living cultural landscape, where Anangu have lived for generations, what we see in the landscape today is a product of their ongoing traditions, especially in terms of vegetation through fire management."

Mike has been park manager since April 2016. We spoke in his office at the park headquarters, a view of Uluru’s south-west corner through his window.

Around 20 years ago, when Mike was a ranger, he and some fellow rangers practised rescue scenarios at Uluru. On one occasion, he says, “we abseiled down one of the gorges and I was just shocked at how many plastic bottles, hats were stuck in the gorge.

“I had no idea at the time how much rubbish there was.”

Of course, in the two decades since, disposable water bottles and other single-use plastics have boomed.

“Because plastics don’t break down quickly, I’m thinking, if that’s 20 years ago, what’s it like now?” Mike asks.

“What they eventually break down into, and what the impacts of those byproducts will be, that’s an unknown.”

Rangers do a climb patrol to check the chain every few months and make sure it holds strong. While they’re there, they pick up any rubbish they see, but by that point, it’s usually blown off into the surrounding area.

Then there’s the damage to the rock itself. The climb’s scar is perhaps the most obvious. Alongside runs a chain, installed in the 1960s to make the climb safer, drilled in the rock.

Uluru is chipped away whenever climbers run into trouble – say, finding themselves in a gully they can’t climb out of. Abseiling rescuers have to install bolts to reach them.

For climbers that make it to the top but hear nature’s call, they’re forced to answer it on bare rock. There are no toilets at the top and no sand to bury whatever they need to do.

But it doesn’t stay up there.

Uluru-Kata Djuta National Park isn’t technically a desert; it’s semi-arid. When it rains, it washes everything from the top of the monolith into pools below.

Water tests in recent years haven’t indicated too much biological impact in the waterholes around the base of Uluru. This could be, Mike suspects, that because during long stretches between rains, waste sitting on top of the rock might simply break down.

But an animal that might be affected is a plucky little creature called the shield shrimp. During long, hot, dry periods, their eggs lay dormant. But when it rains, those eggs – which might have been laid years ago – hatch, even those on top of Uluru.

The tiny tadpole-like animals, complete with a double-pronged tail, can grow to seven centimetres. They mate madly and lay more eggs before dying.

Climbers’ shoes can grind shrimp eggs into the rock. It’s also possible that tourists going to the toilet on the rock was responsible for the local extinction of another type of shrimp that inhabited Uluru’s top rockpools.

When the chain comes down, traditional owners will be consulted to figure out what to do about the holes left in the rock.

There’s also the matter of the scarred path. It might weather like the surrounding rock and blend in, but, Mike says, how long that will take isn’t known.

But one thing that will be saved is time.

At the moment, to decide if the climb is open or not, a ranger checks Uluru’s weather conditions five times a day, then lets local hotels and tourism operators know.

This eats up around four hours each day, or the equivalent of 182 eight-hour shifts each year.

The park could do a lot with that time. For instance, rangers could conduct a couple of cultural walks a day. It would be cost-neutral, funded entirely by not having the climb, Mike says.

So, I ask: on 26 October next year, will he celebrate?

Mike laughs and nods. After the decision was made to close the climb, the Uluru-Kata Tjuta Board of Management decided that Parks Australia should prepare a climb closure plan.

“In the plan is a celebration – not only to celebrate that the climb is closed, but to celebrate a new beginning for the park, to ... cultivate a connection to the cultural and natural values of the park.”