Panic reaches me on the end of a late afternoon sunbeam. The sun’s light is just strong enough to pierce the canopy of this thick fairy forest. I could certainly use the magic of fairies right now. Anything for a bit of clarity through this maze of mountain beech. I’m rapidly running out of water. And daylight.

Leaves smother my face. Branches poke and scratch from all angles.

Through a rare gap in the foliage, I spot the towering buttress of the Dragons Teeth – a prominent mountain in the Douglas Range, located in the north-west of the South Island. Rumour has it there’s a ragged route along the eastern slopes of the Dragons Teeth, a mountain goat’s domain demarcated by sporadic rock cairns. It’s been over an hour since I last saw one. So, in desperation, I set a compass bearing south-west, towards the mighty buttress, and plunge in.

I’m on an 11-day solo wilderness hike. It’s turning out to be a rite of passage, a navigation of both internal and external terrain.

Do I head for the tree laden ridge, or descend to the dark valley? It’s a decision that could get me horrendously lost. I can hear a river below. Or is it just the wind?

I eventually decide that I’ve climbed too far up. The slope’s gradient is now twisting my ankles at awkward angles. I need to lose altitude. Fast. So I slide down mossy chutes on my backside, bumbling through pandanis, grabbing onto stray branches to halt my descent. Sometimes I’m rudely halted when my backpack snags between trees. I’m praying that I won’t meet the sheer edge of a bluff, that I can actually get down from here.

I reach for my map, wedged between backpack strap and chest, to check, but it’s gone. It’s bloody well gone! Panic picks me out again.

I look over my shoulder. Where have I just come from? I’ve been sliding at random and it all looks the same. I backtrack. Curse. Clamber. Swear. Scratch my head furiously. Ten minutes pass. No map. I’ve got this. Fifteen minutes elapse. Prolapse. Anxiety’s boiling.

Desperation often forces my hands into prayer position. “If there are any benevolent beings watching over me,” I say out loud, “then show me the map. Now!”

And I kid you not, I spot it at that exact moment. The swearing and ranting stops. This is a massive let-off. A stern warning to just slow down, shut up and pay attention.

FORGOTTEN MARBLES

The trees relent and I see what looks like a flattish campsite by a river. I refill my bottle, and am just about to set up camp when I see cairns. I’m suddenly back on the “path”.

Buoyed by good fortune and a decent glug of water, I follow the river. It’s not long until the path vanishes once more. Huge moss-covered boulders lay strewn everywhere, the remnants of a giant’s game of marbles long forgotten.

I spend half an hour roaming in circles, unable to see a clear route through. Only then do I realise that I’m wasting energy trying to find a path. I need to trust my instincts, trust that I’m both physically and mentally capable of getting through this. There’s no other choice.

Eventually I find a way through. I also find a rare patch of flat ground and pitch up. I eat dinner on a rock in the middle of the river. I gaze up at the base of Anatoki Peak and wonder how I’m going to reach the campsite near its summit – nearly a kilometre in the air from here – with no obvious trail.

BUSH-BASHING BASTARDRY

My training for this walk involved seven days of dancing at a music festival immediately prior to arriving in the Douglas Range. The lack of sleep has definitely caught up, and it’s affecting my decision making.

The next morning I track along the river. I have to cross it eventually, so I’m keeping my eyes peeled for paths on the other side. I pass a shirt tied to a tree. Maybe this is the spot. I cross the river, but find no evidence of anyone having come this way before, no animal tracks even. So I keep going, lured across the river once more by a cairn stack that seems more for decoration than for way-finding.

And then my patience runs out. I can see Anatoki Peak through the trees, and so lock in its westerly pinnacle to my compass. It’s time to take a deep breath and start bashing again.

I enter the bush in a terrible spot. It starts out promisingly enough, but soon I’m so engulfed that every step requires a huge amount of effort. I’m well and truly in the bowels of bush-bashing bastardry.

A branch lashes my eyeball; my vision was blurry enough already. I look earnestly for breaks in the trees, anything that may give me a couple of free steps and a little fresh air. I’m angry with myself for getting into this position again. But this is the challenge of the walk, and it’s producing a slightly addictive shot of adrenaline each time I seem completely lost.

I spot some rocks to my right and hear trickling. There’s a gap in the trees not too far away. And then I see manna from heaven: a dribbling creek. Manna not just because it means hydration, but it’s also a much more direct route up to Anatoki Peak, direct in the sense it’s not swamped in vegetation. It’s like a giant’s causeway, a secret passage only foolhardy bush-bashers discover by mistake.

I clamber up rocks, avoiding mega slippery black sections. I climb most of the way up the mountain using the creek. But just as I think I’m about to see a clear path to the ridge, my rocky route ends abruptly in bluffs.

My only option is to turn back. After some awkward down-climbs, I eventually bypass the bluffs. The bush relents. It turns into tussock. I’m exhausted after five hours of solid bashing, and so set up a wild camp just beneath the ridge. There aren’t many flat spots, but there is a pool of water. I may be scratched and bruised, but this land is looking after me.

UNADULTERATED IMMERSION

A cycle emerges over the next 11 days: lose path, scout aimlessly, get impatient, set a compass bearing, bush bash, and then, just when I’ve given up on needing to find the track, it reappears.

What does life look like when I’m forced off-track? When I step into the terrain that causes doubts as to whether I can make it through? Stepping into challenging wilderness realms like this brings up these doubts so strongly that I can only smash through them. This trip is about discovering exactly how I want to walk through life. More importantly, remembering to be kind to myself whenever I lose the way.

I scramble out of the dragon’s mouth. I follow animal trails. Head-high tussock plains engulf me. I lose my legs down sporadic, soggy holes. I listen to the distant echo of bird calls ricocheting off nocturnal valley walls. I weave through the saddle of the Needle’s Eye and stumble past the Drunken Sailors. I bathe in Lonely Lake and feel part of everything. I wild-camp on ridge tops beneath moon and stars. I watch morning mist hover over Boulder Lake. Branches draw blood. One whips my mouth during an uncontrolled slide down a mossy waterfall. I end up in places few people would have ever contemplated being, all the while frantically chewing dried mangoes.

Some days my walking speed is less than 500 metres per hour. Some days I marvel in mountain mist.

One afternoon, I spot a curious mountain face coloured like a parrot. The top of the parrot’s head is red (lichen on rocks), its eye rings are blue scree. Tussock slopes coloured yellow and green complete this distortion of reality.

On another afternoon, I take a mountain top perch and look through a gap in the mountains, out towards the distant town of Takaka (my end point), which looks like it’s floating in the sky with the clouds.

COMING HOME

Such wild disorientation is reactivating a survival gene, a forgotten sense stifled by everyday convenience. The further I walk through these mountains, the more I begin to feel their power saturating every cell. The more I realise how too much comfort dulls my senses. I realise too that what’s important is not how far I walk, but how I connect with a place during the motion of travel. And I’ve certainly connected with this terrain. My skin is a living canvas of bloody souvenirs.

For over a week my only company are bush robins (one of which tries to land on my head) and wekas, inquisitive ducks always on the scavenge for bits of dinner. It’s jarring when I finally see people after eight days. Two brothers, aged 71 and 68, have just completed an arduous seven-hour ridge walk. And although their appearance startles me, their buoyancy and vigour is inspiring.

The weather is good yet again so I spend my last night on the range camping on a ridge top directly opposite the Dragons Teeth. My round-the-houses loop is nearly complete. Serenity saunters on the end of a late afternoon sunbeam.

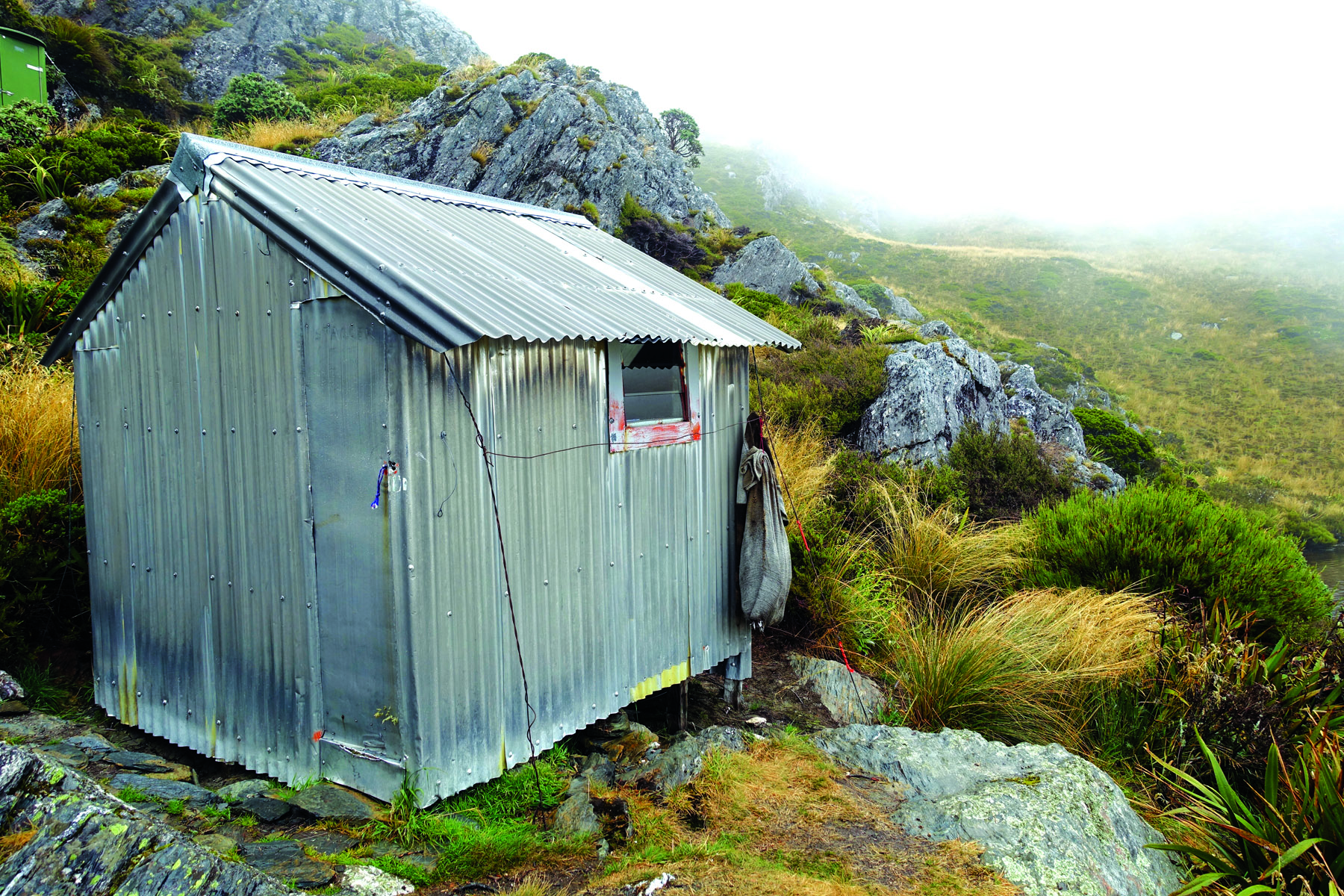

The walk to get to this ridge today was exhausting. A thousand metres of descent, bush-bashing down to the Anatoki River, and then nearly the same height up again, bush-bashing up through the mountain beech. I’m delirious. The decision making part of my brain has shut down. I stagger around the ridge top looking for flat spots. The wind howls sporadically. There’s a small tramper’s hut down by Adelaide Tarn, maybe a 300 metre descent away, but my legs are too exhausted to go any further. I pitch the tent where I stand.

Nighttime falls. The wind picks up. It’s shaking the tent. Now it’s raining. The ground isn’t flat at all; I’m continually sliding towards the bottom of the tent. It’s midnight, but I decide to pack up my things and head down to the hut. Hopefully nobody is down there.

I flick on my torch and walk through the rain towards the hut. Thankfully, I have it to myself.

HO HO HOME ON THE RANGE

My last summit traverse on the range is Yuletide Peak. The route from here follows a broken ridge; another 1000m descent of knee-knocking joy. I spend three hours atop Yuletide, absorbing the majesty of the Douglas Range one last time.

Sitting in this mystic arena of rocky cathedrals, each mountain summit a holy pinnacle, is like I’m awakening in my own Dreamtime. Every footstep I take is a line written in my personal mythology. And while I haven’t slayed any dragons, my intention was never to conquer peaks or fantastical beasts; it was to align with the forgotten wildness of my soul and see that reflected back to me by Nature, as only Nature can.

It’s safe to say that the dragon roars on.