“How many lollies does it take to circumnavigate a mountain?” We pondered this question as we packed for our trek of Nepal’s Tsum Valley and Manaslu Circuit. Our verdict: six people x 21 days = roughly ten kilograms of sugar bribes.

Packs brimming with (melted) chocolate, we stuffed our children, aged 13, 12, 11 and nine, and ourselves, onto a dilapidated, over-crowded bus, and spent the next eight hours crossing our fingers that the bribes would work.

A STEEP LEARNING CURVE

After a couple of easy days walking along a rustic road and scrambling over the odd landslide, we turned off the Manaslu Circuit to follow the old salt trade route between China and Nepal. We then, over the next few days, climbed almost 3,000m to Mu Gompa, a monastery situated at 3,700m above sea level, one day short of the Tibetan border. Our light-headed progress was slow, but the promise of a delicious dessert of wild rhubarb we’d picked along the way kept us motivated. We were surprised to find, however, that our hosts didn’t know what to do with the woody stalks we proffered, so, much to everyone’s amusement, our children occupied the kitchen preparing and cooking the rhubarb themselves.

When the sun disappeared, the temperature plummeted to below zero degrees Celsius, but tucked away in wind-proof stone dormitories and cosy sleeping bags, we had an excellent night’s sleep. Spectacular snow-capped mountains glowed at us from every direction in the morning light, and our eldest child couldn’t have wished for a better place to wake up on her 14th birthday.

We retraced our steps back through the Nepalese-Tibetan villages, with their beautiful stone houses, endless stone walls, and remarkable labyrinths of stone walkways; past wide, flat fields with teams of men and women collecting potatoes and directing ploughs pulled by bullocks and yaks; past the monastery high on a hill in which we had seen a saint’s holy thousand-year-old footprint set in stone; past a convent with its poster at the front gate brazenly advocating the need for a change of attitude towards menstruation and the importance of good personal hygiene practices; past the fields lying fallow, which had been rapidly overtaken by the rampant weed, marijuana; back to the strong metal footpaths bolted securely to the sides of huge stone cliffs, high above the river below; and back down through the monkey forests to the Manaslu Circuit once more.

FINDING COMPANIONS, HUMAN OR OTHERWISE

Despite the relatively low number of trekkers the Manaslu Circuit receives each year compared, for example, with the neighbouring Annapurna Circuit, we felt somewhat overwhelmed by the many groups we now met, versus the isolated few we had encountered in the Tsum Valley.

We were not the only family trekking the Circuit. We met several families with teenaged children, including one who was studying for her Grade 12 exams in a couple of weeks. We also met a family whose youngest child was only seven years old.

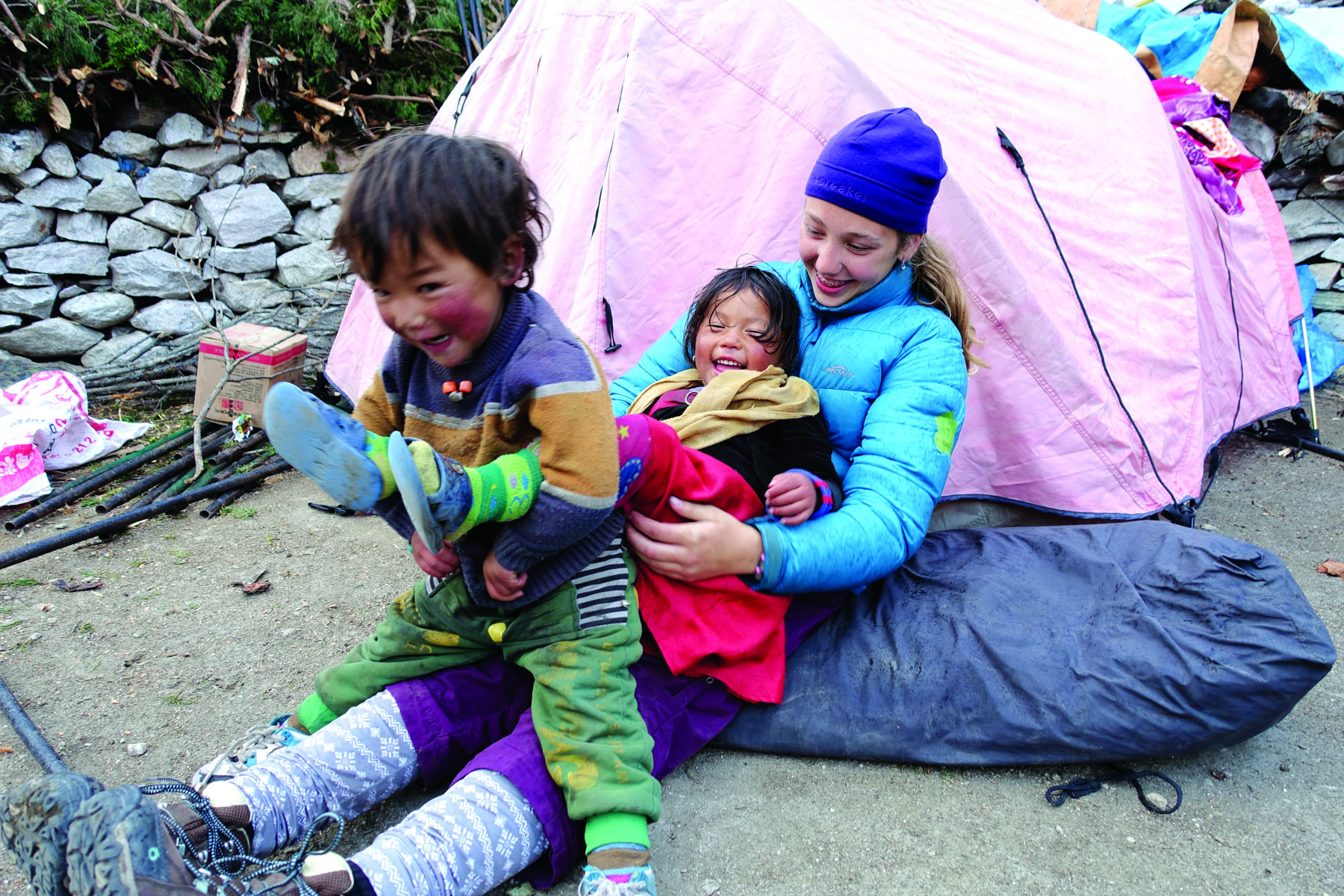

Our children longed to play with other children. They were not deterred by dirty faces, hands or clothes, nor by nostrils streaming with snot. They played tag; they had piggyback races; they gave dizzy-whizzies, and they coo-ed over sleeping babies in baskets, as did I. It was my honour to be permitted to relieve a young couple of their four-week old daughter while they ate their dinner in peace. The new family was returning to their home village high in the hills, after a doctor’s appointment three days’ walk away.

Our children also interacted with adults, educating unsuspecting trekkers about Tasmania’s unique wildlife and enticing them to visit us back home. They learned about the lives and adventures of others and added new card games to their repertoire.

As well as mingling with foreigners, our children spent a great deal of time playing with our porters. These generous men spent all day carrying loads well over 30kg, yet they played throughout lunch stops and in the evenings, when not busy helping in the kitchen. Their energy, enthusiasm and cheerful spirits were inspirational. They never seemed to tire of our children’s endless efforts to teach them words and expressions in English, and when ever there was no ball to kick, they would invent other games to play, like push-up competitions or throwing stones at a target. The children graciously shared their sugar loot with these men.

Animals were another source of entertainment. Early in the piece the children fell in love with a litter of seven fluffy puppies. They allocated names to each one and pestered us to allow them to bring a couple with us, if not back to Australia, then at least for the duration of the hike. “They can trot along beside us and we’ll carry them when they get tired, Mummy. Please...” We didn’t succumb to this plea, but we did let ‘Nicki the Mouse’ travel with us for a day. He gobbled up the grains of rice and wheat the children fed him, but sadly poor Nicki didn’t make it through the night.

CREATIVELY MANAGING MEALS & PROVISIONS

Meal times were a topic of conversation. Our youngest son has Coeliac Disease, but with delicious soups, omelettes and a never-ending serve of dal bhat, this was not an issue. It was his spice-hating sister whose diet was more restricted. She monitored her intake of lollies so as to add variety to her otherwise boring diet of potatoes or plain rice every lunch and dinner, 21 lunches and dinners in a row.

Our gradually-depleting 10kg of sugar bribes was in the charge of a different child each evening, whose job it was to fill everyone’s bag with their daily quota. Each day, the children traded for their preferences among themselves: musk sticks, fruity chews and snakes for Chupa Chups, boiled lollies and pieces of Toblerone. The slabs of chocolate hadn’t fared so well in the heat. Cleavers and chopping boards were needed to divide these conglomerations, so they were reserved for dessert.

Any left-overs could be carried over to the next day, and our 11-year-old stockpiled 18 lollipops and 21 sherbet lemons to ‘give him energy’ for the day we were to cross the Pass. Predictably he became utterly sick of them within the first few hours of the ascent. Despite his disappointment, he was popular among other trekkers and porters for his apparent generosity.

He was also renowned for his generosity in ‘giving away’ blankets. We each had a very warm sleeping bag and thermal underwear, and were never cold in bed. However, a British couple we met had been told by their agent that they need not carry sleeping bags. They spent each night snuggled together wearing every item of clothing they had with them, under the thin supplementary blankets the guest houses sometimes provided. For the several nights that we shared with this couple, our generous son thoughtfully gathered up all six of our blankets and gave them to the Brits.

STAYING LEVEL HEADED AT ALTITUDE

For the entire journey, we were perpetually surrounded by hills and mountains much higher than us. There is an optional side trip some trekkers include in their itinerary to a monastery at the old Manaslu Base Camp. A safer route to the summit has since been declared, rendering this old camp obsolete. It sits at around 4,000m. We had splendid views of Mt Manaslu as we approached, but the clouds quickly obscured the mountains above and the valley below. It was easy to imagine we were on the top of the world until a brief gap in the clouds revealed a glimpse of the mountain peeking out from above the highest cloud, and we were reminded of our insignificance, and of the fact that the mountain rises a further 4,000m above us.

We also attempted to hike up to the ‘real’ base camp. The track was very steep, but the little dog who followed us didn’t seem to notice as he trotted back and forth between our legs, seeking pats and scraps of food. The children happily shared their lunches with “Ritchie”, but were very protective of their lollies. Ritchie turned back with another group of hikers who’d reached the camp earlier in the day, while we pushed on. We had stunning views down to the turquoise lake we’d passed in the morning, and of the massive glacier that fed it. According to reports from other hikers, we were apparently very close to our destination, but when it began to snow, we thought it best to turn around. Two of our party tried to dissuade us from this decision, but their youngest brother vehemently defended it: “That’s precisely how people die on these mountains!”

OBSERVING THE WILDLIFE

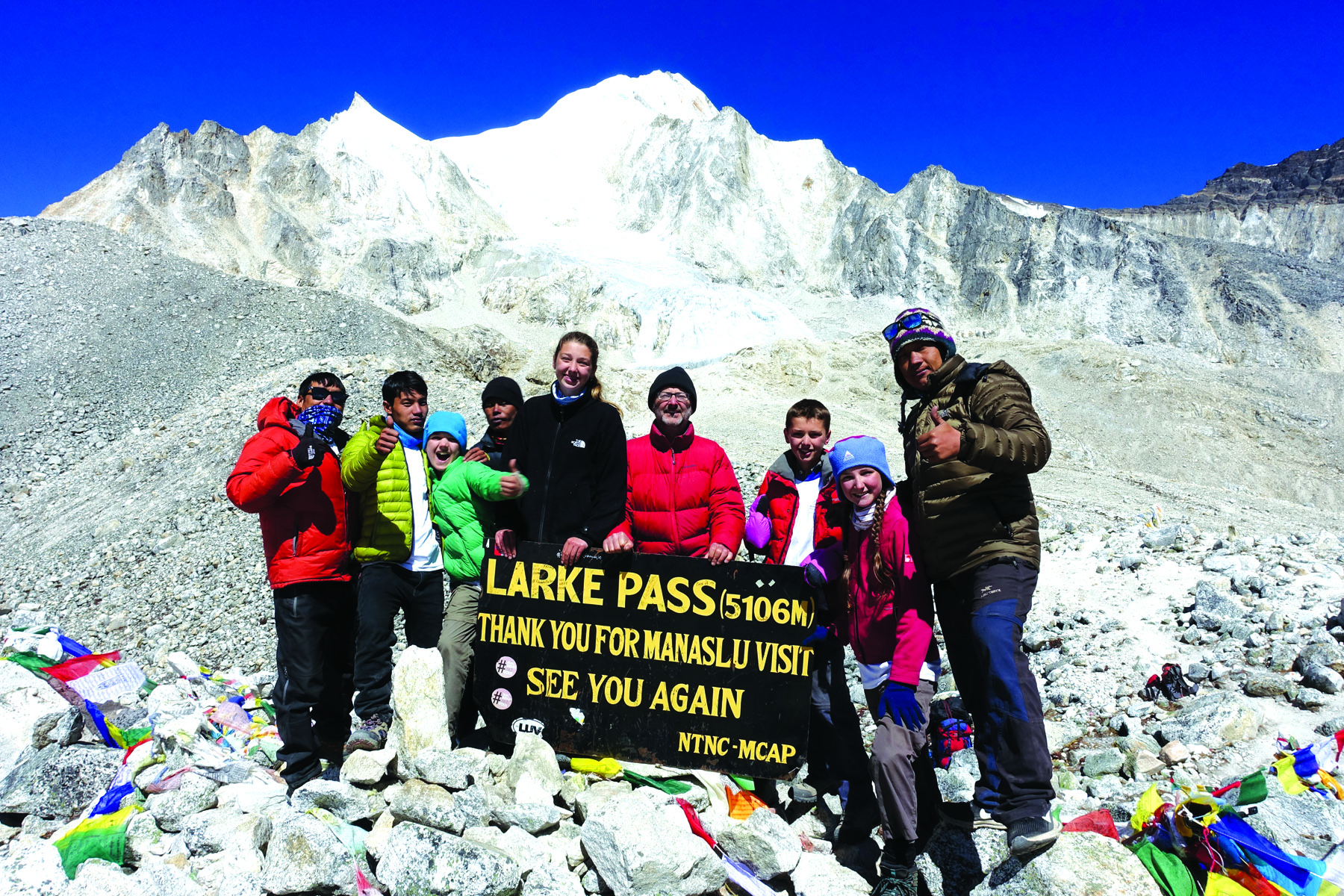

In the lower altitudes there had been much greenery, including forests to walk through. Higher up there were only shrubs and grasses. The Larke Pass was a moonscape devoid of all vegetation except for the lichen trying to brighten the rocks with colour.

In the forests we enjoyed spying on the grey langur monkeys through our binoculars as they ate wild apples and scrambled across rock faces. Their small black faces shone through their bushy white manes. Unlike the rhesus macaque monkeys of Kathmandu, these wild alpine monkeys kept their distance from us; but we noticed that most farm fields had a watch-tower in the middle, complete with smouldering fire, for the farmers to guard their crops against night-time monkey raids.

The forests were home to many beautifully coloured butterflies and dragonflies, as well as numerous species of colourful birds, including the handsome hoopoe, with its distinctive stripes and colourful crown. Such insects and birds were replaced by eagles and vultures as the altitude increased. Mule trains passed walkers between every village, heavily laden with produce from either Kathmandu or China, depending on which was closer. In every train there was usually at least one poor creature limping, but at around $1,000 per mule, traders can’t afford to keep spares so that their injured animals can rest. Every animal must shoulder its 50 or 60kg load and keep up with its neighbours, up hills and down, over uneven stones and slippery, muddy paths, kilometre after kilometre, day after day.

FINDING LESSONS IN NATURE’S CLASSROOM

Like the mules, we walked every day too. Each evening our guide would run through the next day’s itinerary. Breakfast and departure times were usually overly optimistic, but the descriptions of the following day’s route were always accurate. It was particularly helpful for the children to know in advance how long or strenuous the next day would be so that they could strategise over when best to eat which lollies.

Most days were about eight hours from guest house to guest house, with a long lunch stop, where food was prepared and cooked from scratch. Hungry tummies had to learn to wait; a lesson not learned as poignantly in classrooms back home. Neither do classrooms at home teach how to walk, hour after hour, day after day, blisters or no blisters; or how it feels to keep walking when you can scarcely catch your breath; or how to get up at 4am to start walking in the cold and dark, and to keep walking, for ten and a half hours, over a 5,100m pass and down the other side, step after steep step.

By the time we reached the end of our walk a couple of days after the Pass, we still had plenty of lollies left. Our children were such confident and competent hikers that they needed nothing more than their own two legs to get them to each day’s destination. All the same, they were delighted by the opportunity to stand in the back of a ute, singing ‘Happy Birthday’ and ‘Jingle Bells’ at the top of their well-adjusted lungs to the bewildered villagers and amused trekkers we passed as we bounced our way to the bus station.

Back in Kathmandu, it was our second daughter’s 13th birthday. Her brothers and sister offered her their sugary leftovers, but her sole birthday wish was: “No more lollies, please.”

Well, at least until our next holiday...

MAKE IT HAPPEN

Best time to trek

March to May, and September to November are the best times for optimal views, agreeable temperatures and minimal rainfall.

Trekking companies

Quality local trekking companies can easily be found online. Your company will arrange all permits (see next point) and provide a qualified guide. Hiring a porter is an optional service. Tourist information about Nepal can be found at www.welcomenepal.com

Permits

The Manaslu Circuit traverses “restricted” areas where permits are required. All trekkers must be accompanied by a registered guide.

Getting there

The trek starts from Soti Khola, approximately 8 to 10 hours from Kathmandu by bus, or 6 to 7 hours by private jeep. Your trekking company will arrange relevant transport between Kathmandu and the start and finish of the trek.

WHAT TO TAKE

- Temperatures can drop to below zero in the higher altitudes, so warm clothing is essential, even though it may only be needed during part of the trek.

- A warm sleeping bag is invaluable, as many guesthouses provide only a light blanket. Sleeping bags can be purchased or hired in Kathmandu, if required.

- Toilets can be unsanitary, so hand sanitiser is essential, and can be purchased from supermarkets in Kathmandu.

- A good camera is highly recommended. Electricity is available for recharging batteries at teahouses along the trek.

- If drinking from local water sources, purification tablets or a portable water purifier is recommended.

- You should consult your doctor to discuss the use of altitude sickness tablets.